Who are we? opened its doors to the Tate Exchange public today. The project went through a month’s long journey of negotiations, agreements and disagreements, measuring, understanding and misunderstanding, planning and developing. And eventually, it all came together today.

What immediately strikes you as you enter are structures that are built out of organic materials; you can see them, feel them and smell them. The big sign Who Are We? immediately sets the tone: the see-through letters etched into the plywood open a window onto the journey that awaits you. The space and the people within it are calm; this contributes to the tone. You are let into a space where you can wander on your own or you can let someone lead you through the different sections. The artists, the organisers and the academics are on hand eager to share the journey and the story of who they think ‘we’ are.

And what a journey. It starts with an uncompromising reminder of our human responsibility as we witness the journeys of the thousands of migrants and refugees who have died, and continue to die, attempting to cross the Mediterranean Sea in search of sanctuary and a better life. Dead Reckoning is a symbolic exploration conceived and created by Bern O’Donoghue of tiny, hand-marbled paper boats. They are a fragile reminder of the individuals caught up in the biggest humanitarian crisis in Europe since World War II. These fragile boats are the first thing you encounter when entering the space, and the welcoming face of Bern, happy to give you instruction in how to make a boat with your own message. The circle of paper boats is ever expanding, with messages overflowing from visitors eager to make a change.

Next to this allegorical circle is an interactive map of actual journeys, produced for the project Crossing the Mediterranean Sea by Boat. The map, which documents migratory journeys and experiences, was produced under the leadership of Dr Vicki Squire (Warwick), with an international and multidisciplinary team of co-investigators. The interactive map allows you to see the actual distance that people traverse in their arduous journeys to Europe. It is a stark reminder of the endurance and motivation that refugees need to have to reach safety.

Bern and Vicki worked together and there is a dialogue between the symbolic and the real, witnessing the journeys. It reveals the number of journeys, the variety of lived experiences and the unprecedented ignorance displayed by media outlets and politicians when referring to this problem. It also reminds us that we have done very little to challenge this narrative.

As you venture further into the space, you encounter a chest of drawers, with peculiar objects scattered in semi-opened drawers. It is an open invitation from the artist Natasha Davis, to join her on her exploration of how displacement has affected her life. In Natasha’s project 50 rooms (installation), autobiographical experience becomes a tool to draw attention to specific events or crises, but also a tool to celebrate life and one’s ability to not just survive, but also thrive in precarious situations. Crossing borders, living in exile and in-between homes can be a difficult and traumatic experience, according to the artist, but it can also be an incredibly fertile space in which one can reinvent oneself. The artists also propose that people contribute drawer content and extend this concept in new directions, she calls for ‘shared autobiography’, a process that can allow transformation and bring forward shared human values.

Graphic Thought Facility and Universal Design Studio

As you move further into the space there is a series of projects that rationalise and explore migration and the concept of ‘we’ from multiple, multidisciplinary perspectives. You can visit Nele Vos’s Citizenshop and determine the value of your passport or you can contribute your journey and facial features in the project How Do We Know Who We Are? by Dawid Górny & Evelyn Ruppert. All these different projects explore difficult concepts related to how our citizenship of the world is constituted: how we travel, how we communicate with human and non-human entities around us, how we share space, how we open up our hearts and homes to others.

And then, just before you arrive at the last section of the space, you encounter a visual regression by Behjat Abdulla. He asks you to think of what myths we are building for our future generations. He tells a story From a Distance, a story that circulates among refugees from Syria, a myth in the making. A close-up of a child’s face, young people waist deep in the sea, a black square, silver foil. I paused there for a while. I paused there as a mother of two young children. I couldn’t move without asking myself, what are they going to think about us twenty years from now? Who are we in their eyes? Were we too complacent, too indulgent, too involved in our own survival to think of other people? Did we allow too much? How can we stop this?

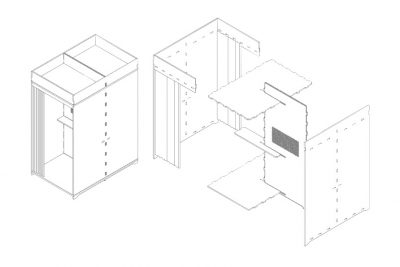

Then I delve into the last section – what I call ‘the way forward section’ or the part where artists dare to offer future propositions. We are ultimately not so different. We may like different brands, and we might get angry at each other sometimes, but in the end, a simple hug, a handshake, a text message can make us feel part of shared humanity. Gil Doran proposes a rethink of the Union Jack, perhaps we just need to insert more colours and textures into the old flag, de-colonise the symbol and make it more human. Laura Sorvala listens carefully to stories of shared humanity and translates them into cardboard ‘feel good’ boxes. And Richard DeDomenici offers you a chance to walk out lighter and happier, just lock yourself in his booth, shed your fears and worries and walk out as a new, better self.

I enjoyed the journey. It is a real human experience, grounded in facts. But also, it talks about the constant struggle to understand what really underpins the migrants and refugees journeys. Citizenship, donations, routes, collaborations. And finally, it offers what we all probably need: clear answers. We are all drowning in questions, so to end the journey with a section that provides answers for the future is openly optimistic. As a species, we thrive in the worst conditions. The future belongs to the adaptable, to those who can move and still maintain their humanity. The future belongs to the refugees.

Related

-

March 1, 2017

Bern O’Donoghue

-

December 5, 2018

Nele Vos

-

November 5, 2017

Dawid Górny

-

December 5, 2018

Behjat Omer Abdulla

-

March 17, 2017

Gil Mualem-Doron

-

December 5, 2018

Richard DeDomenici