Times of political upheaval is often thought to provoke new forms of artistic and creative resistance. Pundits occasionally suggest that one of the benefits of politically turbulent times is “better art”. This kind of positive causal relationship is, however, beside the point. What processes of political upheaval make clear, is, in fact, the role artists play in imagining a future beyond our current moment is continuous and should be paid attention to before and beyond the point of crisis. Artistic spaces can allow an imagining of what is possible – creatively, politically, democratically – when such possibilities appear determinedly foreclosed. Art can: provide important sites of critique; capture moments of and enhance movements of civil disobedience; and, model new forms of participation and being together.

When I speak of mass political upheaval, I don’t just mean the massive increases in racist and xenophobic hate crimes and social, economic, political uncertainties in the aftermath Brexit, Scotland’s announcement of a second referendum in 2018 probing further questioning around the unity of the United Kingdom, and the causes and consequences of the biggest migration of people since the World War Two. It is also the increasingly restrictive legal and political frameworks that are being set in response to these. Last year saw huge restrictions in access to services such as housing, employment, banking, education and health care for people seeking asylum and with ongoing immigration cases through an expansion of immigration control measures in the Housing and Planning and Immigration Bills. Restrictions have been extended to third sector public criticism of government policies, particularly to those who receive public money and in times of elections and referendums and transparency and public scrutiny are being tampered with through proposed changes to the Freedom of Information Act. With civil society’s ability to hold the government accountable through legal and political means becoming increasingly difficult, alternative and more creative routes need to and are being explored in order to challenge xenophobic discourse and the real-life implications political and legal changes.

Further, political upheaval should not be understood as an aberration from long-term histories of colonialism, imperialism, and neoliberalism but rather as the logical intensification of their harmful consequences. Many of these concerns are not new, and have long been confronted by Indigenous artists and artists of colour who have used art as a tool to challenge dominant political and legal narratives or State ‘alternative facts’.

Laura Malacart: Robert

Nele Vos: Citizenshop

It is also at this political juncture that a challenge to spectatorship is taking place. Participatory art practices allow a space for people from different disciplines and backgrounds to create an alternative narrative together, one that can be outside and break down mainstream and dominant discourses. One that can question and challenge them. Through this, participatory art can break down methods of dehumanisation of people who bare the brunt of these changes and challenge restrictive and divisive politics. It celebrates unity and strength in voices of resistance and the benefit of a multiplicity of conversations. Art, particularly participatory art practices, can allow an exploration of what, for many of us, is not given enough space in the conversation of migration.

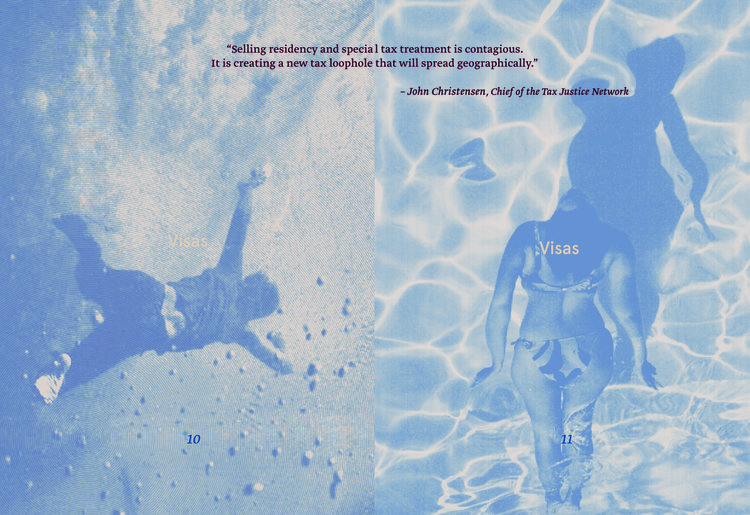

There is a multitude of discussions taking place at the Who Are We? Project. Laura Malacart explores the whitewashing of colonial histories through commerce in Robert; Nele Vos’ Citizenshop highlights the inequalities and hypocrisies of accessing citizenship between those with financial means, and those with a very real need for protection from a new state. Richard DeDomenci offers a safe space for people to confess their fears and discuss difficult issues anonymously with Shed Your Fears. Bern O’Donoghue’s Dead Reckoning is an exercise in memorialising, pushing back against the dehumanisation of those who have lost their lives crossing the Mediterranean Sea in search of safety. Juan DelGado’s Qisetna (قصتنا): Talking Syria provides an opportunity for people to share stories and preserve oral histories of Syrians who have been displaced. These are just a small sample of the diversity of conversations at Who are We?

Towards the end of the Who Are We? project we a holding a Learning Lab, How To Do Rights With Things: Art and Politics. This will allow people who instigated the project and those involved in socially-engaged art practices, campaigns and research to discuss the role of the arts within the present political context. It will be an opportunity to be part of a discussion that will address challenges and opportunities of art and civic activism, of participatory art practices and collaboration and how we protect the rights of people seeking asylum, irregularly migrating and people standing up to protect them.

Related

-

March 1, 2017

Bern O’Donoghue

-

December 10, 2018

Laura Malacart

-

December 5, 2018

Richard DeDomenici