The New Union Flag: From an object of agitation to a space of communication

A conversation about visual arts, mapping and identity between Gil Mualem-Doron (GD) and Giota Alevizou (GA)

The Union Jack has never been officially adopted as the emblem of the United Kingdom but has just ‘fallen into use’. The New Union Flag is a modified version of the Union Jack, which includes designs of former colonized communities and of various ethnic and national groups that live in the UK today.

GA: You describe yourself as an artist and community facilitator. Can you elaborate a bit?

GD: It took me years until I called myself an artist. For a long time I felt completely at odds with the art scene, especially during the ‘YBA years’ and the overwhelming commercialization of the art world. It is only after getting familiar and practicing socially engaged art, community art and transgressive or agonistic art practices that I felt more comfortable with being called ‘an artist’. Rather than producing mere artifacts, my art has more to do with generating debate, creating platforms for communication, and occasionally activism – i.e. the work of a community facilitator. Now, even when I do produce artefacts, such as the New Union Flag, they can be seen as agitprops and in turn they generate dialogue, used in social and political events, and go beyond symbolic representation.

GA: Tell me a bit more about the Union Flag project. How does this animate the concept of community? What aspects of community does it accelerate?

GD: The idea for the flag relates to two previous pieces of work. One was named, Homeland, and it was a street intervention during a cultural takeover of my street in Jaffa, Israel. The other one was an installation at a gallery.

In the latter, I cut out the phrase ‘Homeland’ from a door mat, that when laid back on the ground collects, on the floor, the soil of the people (in this case migrants, refugees, strangers) who walk on it. To put aside the complexities of that work (which was originally related to the Palestinian plight) what this carpet aims to do is to give a platform where the strangers who come ‘home’ change this home (the floor) by leaving a trace from their (home)land.

The New Union Flag also started also from cutouts from a doormat printed in with the Union Jack, which I found online – made in black, white and grey colours rather than the traditional ones. I was looking for other ways of representing the diversity of the gallery’s neighbourhood and Brixton where I lived for ten years, and in Peckham Platform, where the work would be exhibited. In both these areas there are many fabric shops specialising in African and Asian textiles and this sparked the idea. Later I added textiles from Europe, the middle-east, America and Australia. Like the soil in the work ‘homeland’ here the added colours and textile does not relate to abstract objects, such as national flags but to the everyday life of the communities who reside in this country.

After that exhibition the next version was done digitally and printed on flag materials used in many community gatherings, processions and demonstrations, schools, as well as galleries to generate a debate about socio-political issues as well as issues that are internal to the art world.

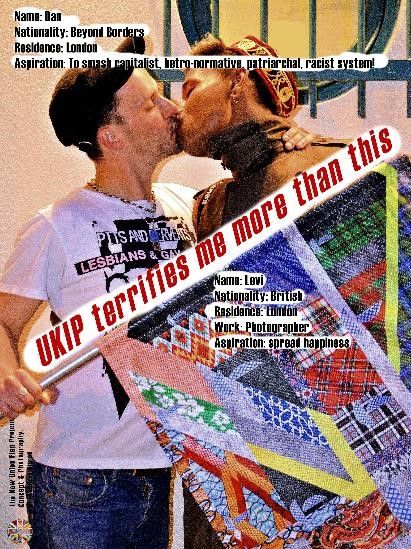

One of the key components of the New Union Flag has been the photo shoot – people holding the flag or standing in front of it, taking selfies, or group photographs or being photographed by me. These pictures are then downloaded on a dedicated website and Facebook from which they can print them as well as see the other people who participated. I would like to think that this creates a virtual yet real community that is created ad hoc around the politics that the New Union Flag is trying to bring about.

The New Union Flag Campaign at Hoxton Arches Gallery, London 2015

GA: You have worked with a variety of publics and especially young people. Can you describe how these audiences experience working within the installation and how they felt /did afterwards?

GD: Before the installation at the Turner Contemporary, commissioned by Platforma, at Margate, which took place three days after the Brexit results, and a few weeks after Jo Cox murder, people suggested that I should wear a bullet proof vest. It was not only that the New Union Flag can be seen as opposed to the politics of what Brexit represents but that the flag has been viewed as a defilement of the Union Jack. Therefore, I was surprised that only a few people were reluctant to be photographed with the flag. However, the name ‘the new union’, the trace of the Union Jack shape, and the representation of textiles from many commonwealth countries, people from different personal backgrounds, ethnicities and socio-political views identified with it. After all the flag does commemorate UK’s imperial past and at the same time celebrates the cultural-diversity this past has brought. Beyond any pre-determined symbolism or message, what the NUF achieves is to be a platform or create a space in which contrasting views and agonistic relations can be exposed and negotiated. As someone who has researched for a long time the notion of ‘public space’, I believe that the flag created such space. Now, it could be that the particular theme of the installation at the Turner Contemporary in Margate, a humorous take on an ‘English Summer’ at a seaside resort contributed to the diffusion of some of the tensions, and open space for conversation, around what could have been a very confrontational work.

GA: In addition to being photographed with the flag, or marching with it, you also developed workshops recently, which will be part of the installation at Tate Exchange. How are these workshops adding to the project?

GD: The workshops until know have been delivered in several schools with great success and I am curious to see how adults will respond to them. I’d like to let visitors to the Tate experience it themselves. What these workshops attempted to do in the past is to reveal, even to people who are very nationalistic and insular, that they themselves relish the diversity that globalisation, the European Union, or even just open minded-ness and curiosity brings to their daily life.

GA: What would the installation and the workshops look like at the Tate Exchange? What sort of experience are you hoping to offer/stimulate?

GD: The Tate Exchange version of the installation comprises of a market stall, which is split in the middle by two flags, back to back: the New Union Flag and the Union Jack. Visitors can choose which flag they would like to be photographed with and all the photos will be downloaded to the webpage.

Moreover, an important part of the project, which will commence with the exhibition at the Tate Exchange is a petition to the parliament to discuss the constitution of an official flag for the UK (the Union Jack apparently does not have any legal status) – to include a discussion on both the New Union Flag and the Union Jack.

GA: In my previous work I have seen people participate in community media and community crafts and they sometimes think of themselves primarily as individual creators, their activities have implicit consequences for the communities of which they are members. Place transcends geography, and presents itself as a crucible for ideology and values. By acknowledging their identity through making a collage in the union flag – people perform their citizenship in a creative way, and, at their same time, they are commenting on the flag and are challenging stereotypes. What do you think?

GD: I am not sure if this answers your question, but I am a bit wary about what assumptions art or creative projects have in ‘giving’ people the opportunity to express their ‘experiences’ or their identity. There have been several projects in the past that seek to cater to minorities (who do not need to be reminded that they are different). Yet often cultural organisations ‘give place’ to such identity performances in a very defined and delimited space.

GA: Does the New Union Flag Project aim to do this differently?

GD: I hope so. For a start, coming from a marginal position, I reclaim a place from which I have been excluded – this ‘place’ is the Union Jack. In the act of modifying the flag, I am not assigning minorities into a designated, and as such, marginal site, but deconstructing a hegemonic site. The New Union Flag isn’t aiming at ‘giving a voice’ or designating a space for ‘the other’, minorities, migrants, refugees – a place where they can preform their identity. The flag aims to subvert a hegemonic institution, and I would like to see it, in the words of Jacques Rancière, as an object of dissensus.

Nonetheless, looking at the reaction of migrants and refugees, who participated in various ways in the project over the last two years, I do acknowledge that seeing traditional textile designs from their cultures woven into the UK’s flag, has had an empowering effect. It gave a visibility to them, and I should say, we, are part of the fabric of British society.

GD: From the start I wanted the installation at the Tate Exchange as part of ‘Who are We?’ to have some components that would spill out of the Tate Exchange to other parts of the institute – from the Turbine Hall to the gallery shop but this infiltration was not approved. So my work in this case has only a trace of the institutional critique that often is part of my work. We need to acknowledge the difficulties and the limits of placing transgressive, activist, and even socially engaged art within the confines of the Museum or gallery.

GA: So, what happens in the translation or movement between the various sites of the project – from the street, to the virtual space, to the Tate Exchange Space?GD: I would like to see the flag, in all of these sites, as an object that engenders new thinking, confronts racism, and generates dialogue. In the street, community gatherings, or the web (in a-material form) – an object was needed. However, taking it into a gallery space it is to run the risk of fetishising it, and muting the possibilities that it generated in other settings. Acknowledging this risk the project at the Tate Exchange can work only by the destruction of the artwork. As I mentioned before, the core of the installation are the two flags, the New Union Flag and the Union Jack, which are hung like a curtain dividing the market stall. People who support the New Union Flag stand on one side, take selfies, or carry out a workshop, looking at the agitprops; and the people who support the Union Jack are doing the same on the other side of the stall. They literally don’t see each other. For them to engage in dialogue they will have to ‘put down their flags’ – they will need to draw the curtain to the side, and open a space of communication. By doing so, the art objects, that are the two flags, are wiped out. It is both a symbolic act and a performance that I hope will generate a tangible effect – people face each other – face to face, and talk. To a certain extent, it is an antidote to virtual relations on the web – where online communities are becoming more and more homogenous. If indeed, people will dare, be encouraged or instructed to draw the curtain aside (which is challenging given the fact that museums visitors have been preconditioned not to touch the art) – if people will do it, and when they do it, the gallery, and in particular, the Tate Exchange, can truly claim to be a public space.

Learn more about Giota and her work, and Gil’s work.

No Comments