Movement and Immobility

Catalan Political Prisoners and exiles

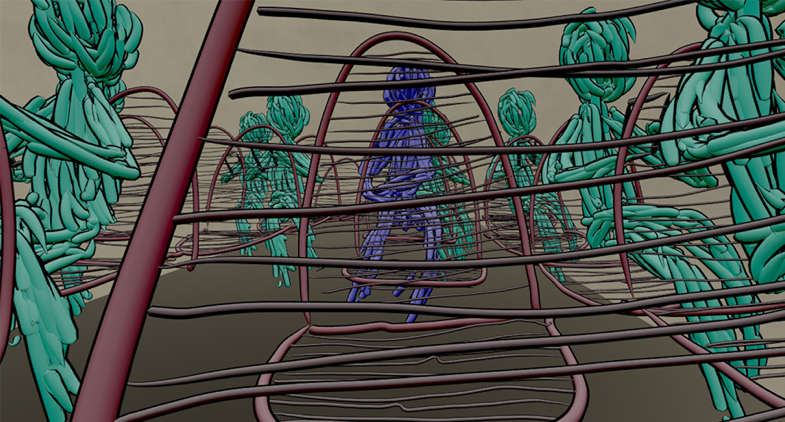

Whilst the images of violence during the Catalan referendum circulated widely around the world, the aftermath of October 2017 is less well known. Politics as lived experience is one way of understanding this aftermath. This is what In Pieces VR, by the artist Joan Soler-Adillon, does by exploring how the events of October 2017 radically affected the lives of some of those directly involved. It is an experimental VR installation about the personal impact of politically motivated imprisonment and exile, which explores the voices of the Catalan political prisoners and exiled politicians, and of their immediate relatives: their sudden loss of civil and political rights, and of freedom of speech in Spain. In the form of a Virtual Reality installation, it presents the testimonies of Jordi Cuixart, an activist in pre-trial detention since October 16th 2017, his partner Txell, and Anna Forn, daughter of the former Catalan government MP Quim Forn, in pre-trial detention since November 2nd, 2017. The VR technology used allows the viewer to move, but only around a very small space (approximately 4×3 meters), so this naturally becomes part of the experience. There is a sort of artistic confinement that goes hand in hand with the story. Although non-realism is a defining aspect of the piece, some of the animations do portray very small spaces.

This artistic confinement mirrors the immobility of the activists and politicians who have been jailed or forced into exile since October 2017. The former group, facing sentences of up to 25 years, has already seen their freedom of movement curtailed as they have been on pre-trial detention for a year and a half already. Their trial began on 12 February 2019 in Spain’s Supreme Court. Those in exile can move freely around Europe, except within the borders of the Spanish state, with an absolute uncertainty of when and if they will be ever be able to return home. Yet the consequences of the Catalan referendum are felt not only by the protagonists in jail or in exile. It is estimated that about 1000 people are being prosecuted, including mayors, teachers, former government officials and ordinary citizens.

The high price of involvement in politics

Repression has been felt by a wide range of citizens in Catalonia particularly those involved in the ‘Committees for the Defence of the Referendum’ subsequently renamed the ‘Committees for the Defence of the Republic’ (CDRs). Many young people, in particular, have found themselves in forced exile, detained or with their mobility, in its broadest sense, restricted: their lives literally on hold. One such is Adrià Carrasco, a young man of 25 years involved in the CDR of Esplugues de Llobregat who went into exile following an attempt by the Civil Guard to detain him on 10th April 2018. On the same day, another young participant in the CDR of Viladecans, Tamara Carrasco, was arrested on charges of sedition, rebellion and belonging to a terrorist organization. Adrià was accused of the same charges after being caught on camera participating in the opening of tolls on the motorway during the Easter vacation. The decision of the National Court, to withdraw these very serious charges against Adrià Carrasco and Tamara Carrasco seven months after initiating the procedure, questions the validity of the original accusations. Yet, despite dropping the charges, due to a surreal judicial limbo situation Tamara still faces a ban which confines her to her municipality, except to go to work, and the obligation to report every week to the nearest court. She notes ‘my jail is twenty square kilometers.’ Such arrests or attempts at detention evidence the disproportionate restrictions on the rights to freedom and expression and movement with regard to the independence process.

Franco used to say ‘I don’t get involved in politics’ and this warning would be repeated from parents to children during the dictatorship. Just being in a meeting, or let alone being on a demonstration, could lead to quite a lot of ‘trouble’. Politics was a dangerous thing. Fast forward to today and it seems like the Spanish political system has become frozen in time. Political involvement as Tamara and Adrià have discovered is once again costly. They are not alone: another example is a man charged with a hate crime for standing next to a Civil Guard with a clown nose on or the Catalan comedian and actor Toni Albà on trial for his tweets.

Unfinished business of the Spanish transition to democracy

The restrictions on the rights of many Catalans involved in political activity are reflected in the very sclerosis of the Spanish political system. Although successful in many respects, the Spanish transition to democracy following the death of General Franco in November 1975 left unfinished business – for example, dealing with the authoritarian past, reform of the Senate along federal lines and ensuring respect for cultural diversity – which points to different interpretations of the original transition. For some, the transition represented closure, a drawing of the line under the past while for others the transition represented simply the first step on a journey towards further democracy. The lack of political leadership to address this unfinished business is one factor which has led to the current impasse over Catalonia, the effects of which come with a huge political cost and, for many, an incalculable personal cost.

Incalculable personal cost

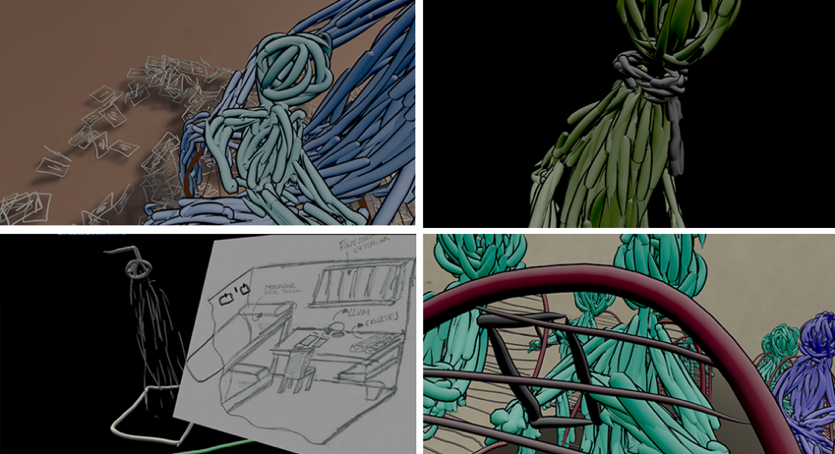

It is this incalculable personal cost which Joan Soler-Adillon explores in his work In Pieces VR. This documentary which uses VR to talk about this more personal level of the conflict, is about the personal punishment and the consequences of the repressive reaction. Two artistic strategies drive the presentation of the content: abstraction and micro-narrative. The first is both on how the virtual spaces but also the characters are presented. There is no attempt at realism. On the contrary: the visitor on this VR installation is presented with spaces made out of paper and handwriting –from real letters received from the prisoners—and illustrations of the spaces described by voice over. It is an artwork in which visitors don’t look at the plinths, but have to knock them down. In doing so, they’ll trigger different micro stories, all constructed from the testimonies of the prisoners and their relatives: the long travel to Madrid to have a 40 minute conversation through the glass, the prison visiting room, or the prisoner’s walk around the prison yard become an experience that is not so much told as lived. But not lived through realism, but through ideas: a line drawn on the floor, but no walls, and sketches of human figures, but not faces. As an eminent Professor said after experiencing the piece: ‘it’s like being inside of ideas’.

The rationale behind this approach was to create an experience that, while being constructed from a very particular case, is narratively detached from it. There are no names, no faces to be identified with the characters talking or appearing in the animations, so the viewer must fill in these gaps, either projecting the actual people portrayed, if they know the case, or projecting someone from their own personal or political context. This strategy seeks to overcome or, at least challenge, the detachment with the other’s suffering that people have developed as a coping strategy through years of contact with traditional media. On the other hand, the micro-narrative approach affords a non-linear experience. There is no right way to navigate through the experience, just four short stories that the viewer will piece together.

The rationale behind this approach was to create an experience that, while being constructed from a very particular case, is narratively detached from it. There are no names, no faces to be identified with the characters talking or appearing in the animations, so the viewer must fill in these gaps, either projecting the actual people portrayed, if they know the case, or projecting someone from their own personal or political context. This strategy seeks to overcome or, at least challenge, the detachment with the other’s suffering that people have developed as a coping strategy through years of contact with traditional media. On the other hand, the micro-narrative approach affords a non-linear experience. There is no right way to navigate through the experience, just four short stories that the viewer will piece together.

In Pieces VR was first exhibited at Gazelly Art House, in London, during October 2018. It has since been exhibited in a VR Journalism event in New York, and at the House for Democracy and Human Rights in Berlin. There are no future plans for exhibition in Spain.

In Pieces VR was first exhibited at Gazelly Art House, in London, during October 2018. It has since been exhibited in a VR Journalism event in New York, and at the House for Democracy and Human Rights in Berlin. There are no future plans for exhibition in Spain.

Georgina and Joan will be in dialogue at the Tate Exchange on the 23rd May at 2.00 to discuss the personal and political aspects of the current situation in Catalonia in a symposium on movement and identity.