Let’s talk about precarious

work in the Arts

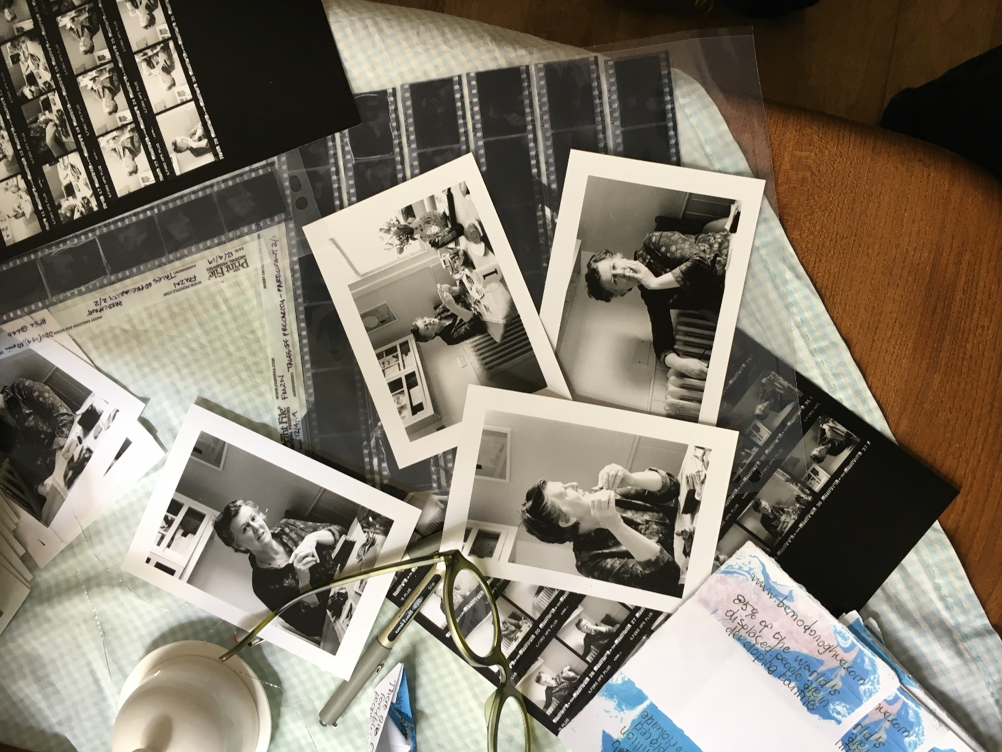

Image by Tim Butcher

The ‘Who are We?’ programme is shaped by co-creation, co-production and exchange among artists, arts and culture organisations, audiences, activists and academics. Over the past three years socially-engaged artists have been central to creating conversations that reflect on identity, belonging, migration and citizenship. In my project, ‘Tales of Precarity’, I turned my lens towards seven of those artists to understand why they do the work they do and how they make sense of their lives as artists working in an increasingly uncertain and evermore precarious world.

Precarious workers are defined by the International Labor Rights Forum as people who fill permanent job needs but are denied permanent employee rights. The casualisation of work — the gig economy — is becoming commonplace as organisations seek to minimise labour costs and maximise their own flexibility to adapt to increasingly uncertain and unstable global economic conditions. The consequence for many of us is an erosion of job security and the normalisation of a reliance on temporary, short-term work contracts. The idea of ‘a job for life’ is fast becoming a thing of the past.

Working in the Arts has long been casualised and precarious, with artists typically being dependent on commissions and grant income to pursue their practice, and often needing to take low paid part-time jobs to afford the necessities of life. The socially-engaged artists I interviewed and photographed each discussed the fact that they do not make art to sell, but to be meaningful to the communities they work with or to engage us in public dialogues about, for example, social injustices such as those they worked on as part of ‘Who are We?’. And so there is a double bind for many socially-engaged artists who, on the one hand, feel compelled to make art that holds potential to transform how we experience the world whilst, on the other hand, must find ways to support themselves that give them the flexibility to respond to commissions from arts organisations at short notice. Many socially-engaged artists are therefore denizens of the gig economy, taking low-paid casual work that they can pick up and put down depending on whether, when, how and how much they are commissioned to do what is meaningful to them — to make art. There are though few guarantees of future work for them in either domain.

Something I learned from the research participants was that they need to not only be responsive to the short-term and often ad-hoc demands of arts organisations, but also perform what I call ‘good citizenship’ to those organisations, demonstrating a willingness to drop other work to focus on specific projects (if only for a day), to collaborate with others, and to be open to co-creating new ideas and artworks for little more than their fee and the satisfaction of having gone someway to making a difference. Fortunately, organisations such as Counterpoints Arts understand the demands placed on artists and the precarities they face, and therefore aim to ensure the artists they work with are treated fairly, equitably and consistently.

Specifically, in developing my methodology for the ‘Tales of Precarity’ project, having previously conducted research with freelancers and start-ups, I was mindful that precarity is not easy to discuss when in our everyday lives we are expected to be ‘good citizens’ who perform competency and project success on-demand, whilst also privately and perhaps anxiously considering where our next idea or project will come from, and whether or not we can pay this month’s rent. Hence, I recognised that I needed to quickly build participants’ trust in me and my understanding of them. I needed to find a way to achieve both objectives. Using film photography and a fully analogue development and printing process, up to the moment of publication, I used the materialities of the process both to engage participants in the drama of making their photographs, and to recall and reconsider what they told me as they later reappeared to me in the darkroom. Across three visits to each of the seven artists I interviewed, I made several photographs, painstakingly developed and printed them in my darkroom, and then took the images I’d made back to them to learn what those images evoked for them, to extend their stories, and to select together the images I would publish. In doing so, I am very aware that I have become a custodian of their tales of precarity — stories they might not tell elsewhere.

The research process unfolded differently with each participant as they took me into spaces that are meaningful to their arts practice, as they told me about their work, and as they shared their life histories that inform why they have followed their particular career paths when they might well have chosen more stable and secure forms of work. Whilst it is too early to draw out specific themes from this research project, it is arguable that it is becoming harder to do meaningful work in any sector, not just in the Arts. As work is casualised, it is increasingly broken up into very-short term projects or even tasks that we are expected to come into as organisations require us to, give our all as ‘good citizens’, and leave without any guarantees we will be invited back for future projects. Each of the seven artists I interviewed told me of their approaches to performing their ‘good citizenship’ in the Arts and in the other work they do. They also revealed their hopes and fears, and their deeply felt and perpetual sense of precarity in a world in which being a socially-engaged artist is undervalued.

The emotional labour that goes into being able to make meaningful artwork is intense, yet each artist I interviewed has a strong will to persist. I believe that as meaning is being stripped away from many forms of work through casualisation and jobs are reduced to performing mundane tasks, we might look to socially-engaged artists to understand how and why they persist in making art when faced with political, economic and social forces that make it harder and harder to do so. ‘Tales of Precarity’ will continue to make and bring together the visual stories that research participants share about their motivations, their perseverances and their uncertainties to co-create with them arts-based ways to generate a public debate about recognising and rewarding socially-engaged art in contemporary society.

The seven ‘Tales of Precarity’ published as part of the ‘Who are We?’ programme in May 2019 can be viewed via the @whoarewe_tex Instagram account. If you are an artist or freelancer experiencing precarious work and would be interested in sharing your story, please contact Tim at tim.butcher@open.ac.uk.