Young participants engaging with ‘The New Union Flag’ installation shot: Photo: Marcia Chandra. All rights reserved.In the time since the Brexit referendum, and in the midst of an alleged “refugee crisis”, when our social fabric is becoming increasingly divided and ‘protective’ against an imagined invasion of ‘others’, Who Are We? – A Tate Exchange project, which welcomed more than 5,000 visitors in its 6 day incarnation last March – responded to processes of othering and division. It emerged as a collaborative exploration of notions of identity, belonging, migration, and citizenship.

Located on the fifth floor of Tate Exchange and at the periphery of Tate Modern, the exhibition space became a civic landscape where viewers were encouraged to physically navigate a shared space and become – as Rancière would argue, active interpreters inventing their own translations of the artworks. A collective of twenty-two installations addressed different facets of migration, inviting audience members to respond to important questions around belonging, human rights and (im)mobility.

Writers including Claire Bishop (2006), Grant Kester (2014) and Nicolas Bourriaud (2002) have contributed to our understanding of participatory, collaborative and relational art and the potential of socially engaged art practice. As Bishop suggests, the artist should be understood as a collaborator and a producer of situations where audience members become involved in shared knowledge-production processes. Equally, the curatorial framework of Who Are We? was invested in translating complex social issues into an engagement experience, facilitated by artists and activists, during which audiences transitioned from passive consumers of art to critically-engaged participants.

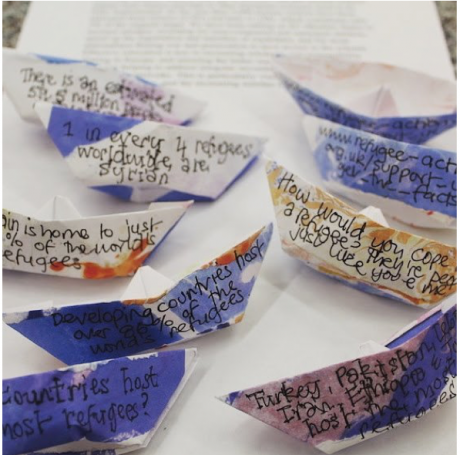

By embracing creative modes of the “responsive artist” and “post-studio practice”, the Who Are We? programme facilitated democratic participation by inviting audiences to become engaged with the exhibition’s programme as well as with the artists themselves. In doing so, the programme challenged the ‘borders’ between art and spectatorship, by letting audiences in and asking for their opinion. Audience members participated in a series of activities including sharing stories, creating artwork as response to posed questions as well as discussing the meaning of hospitality and welcome.

‘Dead Reckoning’ Installation elements shot: Photo: Marcia Chandra. All rights reserved.In his work titled “Engaged with the Arts: Writings from the Frontline”, John Tusa reminds us that “The skill of arts management is to turn the awkward, obfuscating and bureaucratic into a language that truly serves the arts and their audiences.” As museologist Jan Jelinek argues, museums can “only fully develop their potential for action when they are actually involved in the major problems of contemporary society. Museums are institutions intended to serve society and only thus can continue to exist and function.” Such an understanding of the museum as an institution which should share power and knowledge with communities is further explored in creative consultant and reviewer Chrissi Tiller’s piece on the role of the gallery or the museum, in not only ‘making things visible’ but also becoming a platform for social change.

The partnership between Tate Exchange and Tate Exchange Associates was therefore invested in the recognition of the gallery as a space that pushes the boundaries of representation, and instead involved the public in the interpretive process, thereby challenging the gallery’s authority and supporting its role as a space for meaning-making, learning and activism. The installations therefore served as points of departure for audiences to respond to, reflect and interrogate the complexities of a seemingly ‘simple’ question: Who Are We?

In particular, the interactive and participatory audio-focused installation ‘Beyond The Babble’ – produced through the collaboration of academic Giota Alevizou and artist Lucia Scazzocchio – engaged participants in meaning-making processes by inviting them to record personal thoughts, stories and memories around questions of individual and collective identity. Such processes occurred within the surrounding gallery space as participants ‘tuned into’ particular narratives emerging from the ‘babble of noise’; within the installation’s ‘audio booth’; and finally, within the social media sphere, as participants sent ‘audio postcards’ (audio tweets).

During their participation, audiences became engaged in personal declarations while also reflecting on the role of social media as spaces for learning and knowledge exchange, also functioning as ‘echo-chambers’ that can vindicate particular dominant narratives and solidify ‘louder’ public opinions. For others, the embodied experience of ‘speaking up’ allowed them to reflect on the mediated nature of social media and their effect of reducing often complex social issues into simplified ‘Newsbytes’ that lack analytical depth. In their co-authored reflective piece, Alevizou and Scazzocchio, investigate how the installation instigated instances of digital citizenship by inviting self-reflective individual declarations that emerged within the ‘noise’ of social media and created shared empathy for listeners.

Another example of collaborative meaning-making processes emerged through Alketa Xhafa Mripa’s 'Refugees Welcome' mobile installation, which comprised a Luton tail lift van, a neon sign of ‘Hope’ and metallic letters spelling out ‘Refugees Welcome’, positioned alongside the van’s interior and seeking to extend a ‘British Welcome’ to audiences.

Participants responded to Mripa’s kind invitation by sharing their personal understandings of ‘welcome’ as well as reflecting on their (hi)stories and social ties to Britain. Through combining self-reflection and memory exchange, ‘Refugees Welcome’ interrogated popular understandings of the van as a symbol of illegal border-crossing and instead re-imagined a space for hospitality and welcome, invested in the recognition of our shared humanity.

The Who Are We? project, also serves as a case study illustrating what can be achieved through a multidisciplinary creative synergy between academics and creative practitioners, as the latter were paired up during the project’s research and development phase, leading to the final exhibition. As Counterpoints Arts Co-Director Aine O’Brien argues in her review piece included in this series, the collaboration between artists and academic partners “opened up unique avenues and ways of reciprocal thinking and sharing/learning.”

Who Are We? allowed multiple collaborations as it brought together a group of artists working in response to a particular question while also enabling collaborations between different disciplines and art-forms. As Kester reminds us, collaboration carries with it an “implicit ethical orientation in relationship to differences” by moving away from the model of the solo artist and instead evoking an art practice that is “defined by open-ness, listening and intersubjective vulnerability.”

Equally, an ethical orientation towards difference, dialogue and exchange, was evident in the creative methodologies of the Who Are We? project, which resulted in powerful creative interpretations of social issues underpinned by academic insights. Reflections on some of these creative synergies are further explored in this special feature.

By positioning social issues at the forefront, Who Are We? explored the emergence of new commodified forms of citizenship as well as the reshaping of old ones. It also shed light on the prevalence of prejudice and stereotyping in everyday life encounters and encouraged viewers to reflect on the role of borders and decision-making frameworks determining who is allowed in and who remains out; not just from national borders, but also from our hearts and minds.

Who Are We? Banner located at entrance. Co-designed by Graphic Thought Facility and Universal Design Studio. Photo: Cathrin Walczyk. All rights reserved.Since the beginning of the “refugee” or “migrant crisis” the media agenda has been ‘flooded’ with stories of thousands of individuals traversing across European borders, alarming audiences with the prospect of an unstoppable “wave” of “illegal migrants”. As always, it depends on who is talking, and whose point of view is represented. The employment of inundation metaphors such as “waves” or “flows” often reduces displaced individuals to a generic ‘tide’ of human bodies and robs them of their humanity, while supporting a culture of fear and disbelief.

“This is a fear of the unknown: a fear of the other, a fear of the future.” According to the 2017 Demos report Nothing to Fear but Fear Itself? this is the same climate of fear that has long permeated the public imagination in the UK and whose consequences we witness in the UK’s vote to leave the European Union on June 23, 2016, as well as across a Europe pockmarked by the growing rise of ‘populist’ right-wing and Eurosceptic political parties.

Following the Brexit referendum, the UK has witnessed a critical rise in hate-crimes and racist attacks, introducing to the public domain a rhetoric on full national sovereignty, freedom and control, thus re-solidifying binary divisions of “us” versus “them” and creating a hostile social environment that has become embedded politically and culturally.

In an increasingly mediated society, we are surrounded by a plethora of media all posing important questions about who we are as a society: What does it mean to belong to a nation, to Europe, to the UK, to the world? Who has the right to a better life and who doesn’t? Who is allowed in and who remains out? Whose decision is it?

These are some of the questions to which Who Are We? responded to, through creating a platform that challenged dominant discourses. It initiated much-needed conversations between artists, researchers and activists, exhibition spaces and diverse audiences, and art institutions and curators. The project adopted a multi-layered participatory model rooted in dialogical methods of co-production and exchange, bringing together a wide range of expertise, viewpoints and experiences.

For Derrida and Dufourmantelle “hospitality” is perceived as a question of what arrives at the borders of encounter; in that initial dynamic of contact with an ‘other’, a ‘stranger’, a ‘foreigner’ or ‘someone without a name’. The concept of hospitality was central to the project as audiences physically and subjectively engaged in different moments of encounter with imagined and ‘real’ others, while the gallery space extended a welcoming invitation for public participation, creative re-interpretation and multi-vocality.

By resisting traditional linear pathways of knowledge transmission, Who Are We? invested instead in actively listening and responding to important questions about our changing social sphere, while also inviting diverse audiences to become part of the project’s discourse and legacy.

Read more

Get our weekly email

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.